Publications

Articles / Following Lt. Ryan

Sz. Serwatka | AeroPlan nr 1/2002

The Internet site, dedicated to the US Air Forces and primarily to its heavy bomber units, is full of postings of the families that ask for help in finding out the wartime service details of their elder today relatives. Sometimes they are children who seek the surviving members of their father's crew to make an original birthday present. Sometimes the family looks for the service details of the recently deceased, in order to commemorate him in the family archive. Sometimes a dusted box found in a forgotten corner in the attic reveals the wartime past of the ancestor and wakes up the desire to learn more.

Among these people is John Ryan, who made an Internet site WWII Memories of Lt. James J. Ryan dedicated to the aviation wartime service of his father. For the AMIAP (Aircraft Missing In Action Project) Members, finding the Ryans' website was extremely interesting. It included the information that Ryan senior had been shot down during a mission to Blechhammer North (today Blachownia Slaska). The crash site was in the area of Annaberg (today Gora Swietej Anny). Ryan junior agreed immediately to take part in locating the exact crash site of his father's B-24 and the local witnesses of the event.

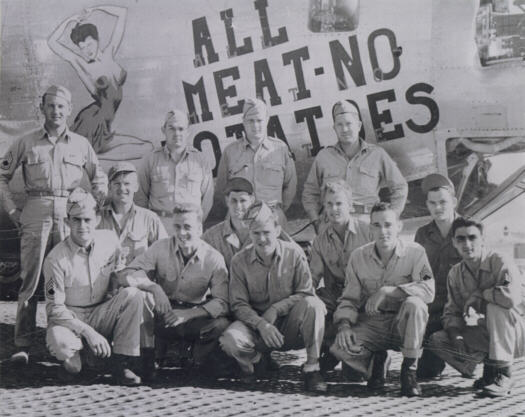

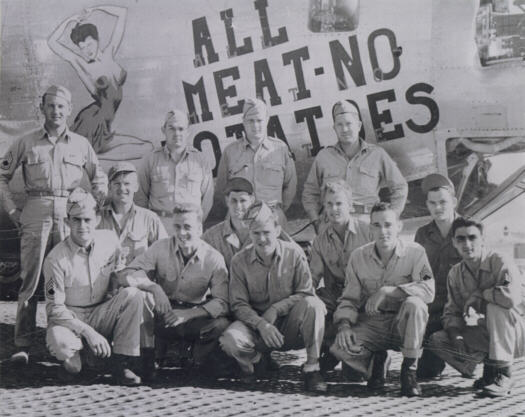

The flight and ground crew of the "All Meat No Potatoes". First row from left: S/Sgt. Dupois, Sgt. Anderson, Sgt. Adams, Sgt. Kramer; second row from left - the ground crew; third row from left: T/Sgt. Patrick, Capt. Tudor, Lt. Ryan, Lt. Williams.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

According to the materials John made available, on August 7th 1944 his father, James Ryan, was a co-pilot in the crew of Captain Tudor (464th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force). Their B-24 "Liberator" was nicknamed "All Meat No Potatoes". The nick name came from a title of one the popular songs of that time.

Lt. Ryan crew in the training base at Topeka, Kansas (end of 1943 or beginning of 1944).

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

The B-24, which Ryan flew, fell victim to the intensive heavy flak fire. According to the accounts of three other aircraft from the same formation, the B-24 received a direct hit over target in the left outboard engine. The engine fell apart. The bomber turned then on its back and began going down in a spin. Then the other crews lost sight of the mortally wounded aircraft.

Lt. James Ryan told his son after the war, that, while the crew had been trying to leave the falling aircraft, Capt. Tudor (pilot) and himself had fought to stabilise the machine in order to minimise the centrifugal force, so that the crew could get out. Thanks to the pilots' efforts the B-24 came out of the spin and kept falling in slow clockwise circles. Five airmen managed to bail out. The remaining five were either already dead, or wounded in the degree that made the bail out impossible.

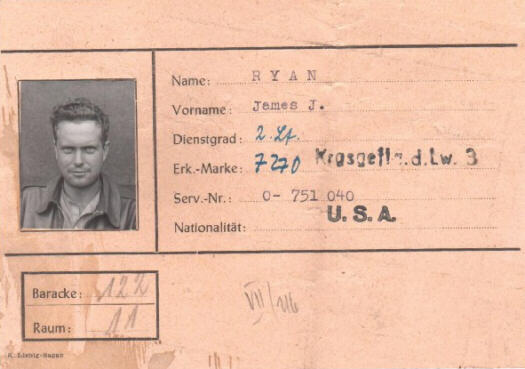

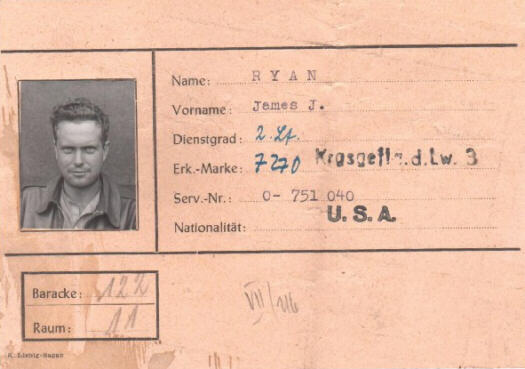

POW identification card of Lt. James J. Ryan.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

While hanging under the safe silk canopy, Lt. Ryan observed the falling bomber and thought what would happen next. The chance of avoiding the capture was very small and he was seriously afraid of the hostile German population.

Very soon he has landed near an abandoned farm, far away from his crew-mates. He has hidden the parachute, the flying suit and other equipment that he no longer needed. He has decided to wait until evening - darkness would increase his chances. Then, dressed in a found jacket and straw hat, he left his hiding and tried to get as far from the crash site as possible. It did not last long before he was spotted by a German army patrol and was captured.

American POWs in the camp at Sagan.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

Louis Valente was the bombardier in Lt. Tudor's crew. In an interview given to John Ryan, he has described the shot down of his aircraft in great detail: "...I was suddenly thrown against a side wall of the bomber. I could not move. It seemed like eternity but the time when I was pinned to the wall by the centrifugal force must have been short. I wanted to help the front gunner and open his turret's door but I could not. Then the gunner, Sgt. Kramer, opened it from the inside. We knew we were in trouble and wasted no time. I have begun to wind the nose wheel door open but it was very difficult to do because of the the slip stream and we had to force the door open with all our strength. The aircraft was falling down upside down or was in a spiral - in our small compartment it was difficult to judge accurately."

"Captain Tudor gave the bail out order. Myself and Kramer had our chutes on already so we have dived into the open nose wheel bay immediately. Tudor got out through a top hatch in the cockpit. Ryan and Hollmann got our through the bomb bay. None else managed to leave the aircraft. I have learned later that Anderson, our engineer and top turret gunner, died from a direct hit from Flak. I do not know what had happened to the rest."

"I was falling down without opening my chute. The bomber was falling at the same speed in a clockwise spiral. I was afraid the aircraft could hit the opened chute so I waited until the B-24 was slightly below me. I still remember how quiet and peaceful was up there. I knew what would await me on the ground so I have enjoyed the moment as long as I could. I have landed close to Lt. Hollmann in a farmfield. There was no sight of none else nor the aircraft." "After landing I drew my Colt .45, although I could not hit a barn with it. Hollmann lost his gun a month earlier when he had to bail out over Yugoslavia, so he was unarmed now. He has advised me to put down the gun because it would cause more trouble than help us. As soon as I did it a few soldiers appeared that were led by a senior gentelman in a German WW1 style helmet. He shouted something like "Hans Hauk!" ("Hände hoch" - hands up) which must have been a request to surrender. We were searched and they searched Hollmann a bit longer because they could not find his gun. I wanted to get a cigarette from my pocket but one of the guards pointed his gun at me - I have understood it was not the best moment to smoke."

"We were taken to a battery of 88 mm flak guns. We have soon found out they were the ones who had shot us down. It was almost noon, so they gave us sandwiches. Two Luftwaffe officers arrived soon who took us through a village - its name was Annaberg, I think. When we walked through the village, a woman ran towards Hollmann and hit him on his head. I had still a piece of the chute on my arm and a small boy took it from me. We boarded a train and joined there two other Americans, who had been shot down too. Strangely, the Germans did not take my watch away from me and I managed to keep it with me through the POW time and it came home with me..."

Full name of the POW camp in Moosburg.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

Valente joined a large group of shot-down airmen, who were collected from all over occupied Europe and taken to Oberursel near Frankfurt am Main, where the central interrogation camp was located. Together with Ryan, Hollmann and Kramer he was then taken to Stalag Luft III in Sagan (today Zagan, Poland). Then they survived the 600-kilometres-long death march when, in March of 1945, the Germans evacuated the camp in the flee from the advancing Soviet Army. They were liberated at Moosberg, Germany. Then they were taken by aircraft to France where they stayed until the end of hostilities. In the end, they boarded ships and headed for home.

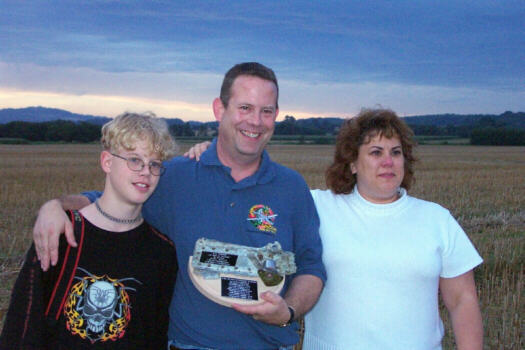

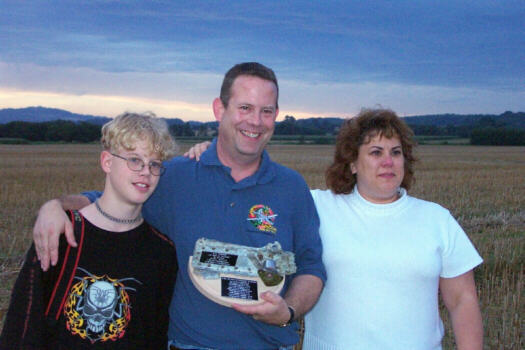

John Ryan with wife and son at the crash site of his father's B-24 - Lichynia, August 10th, 2001. John holds a souvenir piece of his father's B-24 that was found at the crash site.

(photo: Waldemar Ociepski)

John Ryan was very much interested to find out, where exactly his father had landed. An on-site research had to be organised in order to answer this question. Incidentally, the author of the article has contacted Waldemar Ociepski, a passionate aviation history researcher. Waldemar lives in Kedzierzyn-Kozle and has a lot of interest in the USAAF bombings in the area of Blechhammer and Odertal. He has made available a number of interviews taken from the witnesses of different American aircraft crashes. Some of the interviews came from the area of Gora Swietej Anny (Annaberg) but all witnesses pointed to a crash site near a village of Lichynia.

The meeting in Lichynia. Left to right: Michal Mucha, Waldemar Ociepski, Robert Ryan, John Ryan, Szymon Serwatka.

(photo: S. Dragula/"Nowa Trybuna Opolska")

One of the witnesses, Alfred Biela, remembered that it was a very warm day, when the bomber fell near Lichynia. The aircraft were seen from far away - they reflected the sunshine. Mr. Biela remembered an aircraft coming down in circles, because the engines on the left side have been damaged. He saw airmen bail out. When the bomber was still abour 500 metres above ground, an engine fell off. When the plane finally crashed, it caught fire and the ammo began to explode. According to this witness, the fallen airmen were buried in a village of Zalesie Slaskie. The documents stored in the local catholic church confirm, that on August 9th 1944 five American airmen have been buried there, who have died two days earlier.

The accounts of the witnesses could relate to the "All Meat No Potatoes" but there was no certainly about this. The key elements were a map produced by Mr. Ociepski and a copy of a German report provided by John Ryan, where the capture of his father was documented. Both documents pointed at the same location - a field near Lichynia.

The B-24 "All Meat No Potatoes" was well remembered by Mr. Gerard Ciupka. On August 7th 1944 he rode his bike to see if his aunt was OK after the refinery in Odertal had been bombed. The aunt was OK and both walked to the crash site near Lichynia. The ship was burned out and two burnt corpses could be seen in the fuselage aft of wings. Mr. Ciupka directed Mr. Ociepski to another witness, Mrs. Helena Janda. She worked as a nurse in a hospital that was located where the Pilgrim House is today in Gora Swietej Anny. Mrs. Janda could remember two American airmen that were brought to the hospital. Although she could not remember any names, one of these men must have been Capt. Tudor - the German report mentioned he had been taken to this hospital. Mrs. Janda remembered the airman to tell that the Gora Swietej Anny had been an orientation point for the American crews.

Mr. Maksymilian Makosz was another witness of the crash that could be found. He and his uncle were at the crash site as the first local people. Very soon an American airman landed in his chute next to them. He was tall and very fit. He looked like being very content that he had survived. Taking into account that Tudor was wounded, Valente and Hollmann landed far away from the aircraft and James Ryan surrendered only a few hours after landing, the person who landed near Mr. Makosz must have been Sgt. Kenneth Kramer. The witness remembered that when the airman took off his chute harness, a policeman riding a bicycle appeared who shouted from the distance to the American to surrender. They went to the village of Lichynia. Mr. Makosz met again the airman in the village. The prisoner was waiting at the steps of a small chapel near the house of the local administration head. Then Mr. Makosz came back to the burning wreck and he noticed then 22 small bombs painted on the nose. It was the 24th mission of Capt. Tudor's crew and the 23rd bomb must have not been painted yet.

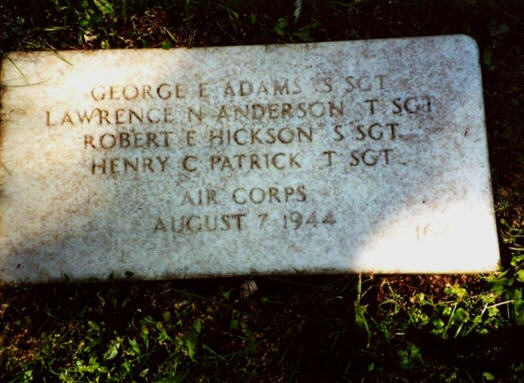

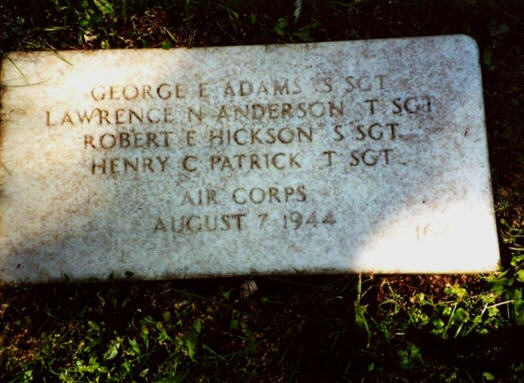

Memorial stone in Zachary Tyler National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

The new cemetery in Zalesie Slaskie. The KIA airmen of the "All Meat No Potatoes" were probably buried in this grave along the soldiers of the Silesian Uprisings.

(photo: Waldemar Ociepski)

Modern view on the Zdzieszowice (Odertal) coking plant from a viewing point at Gora Swietej Anny.

(photo: Waldemar Ociepski)

This is the story of the crew of the "All Meat No Potatoes", recreated after almost 60 years. John Ryan came to Lichynia on August 10th 2001 to visit the place where his father had been shot down. He could also see the industrial complexes over which so many airmen' tragedies happened. He has paid a tribute to these, who had paid the ultimate price in the World War Two. Let us also remember the men who gave their lives so that we could be free.

Return >>

Among these people is John Ryan, who made an Internet site WWII Memories of Lt. James J. Ryan dedicated to the aviation wartime service of his father. For the AMIAP (Aircraft Missing In Action Project) Members, finding the Ryans' website was extremely interesting. It included the information that Ryan senior had been shot down during a mission to Blechhammer North (today Blachownia Slaska). The crash site was in the area of Annaberg (today Gora Swietej Anny). Ryan junior agreed immediately to take part in locating the exact crash site of his father's B-24 and the local witnesses of the event.

The flight and ground crew of the "All Meat No Potatoes". First row from left: S/Sgt. Dupois, Sgt. Anderson, Sgt. Adams, Sgt. Kramer; second row from left - the ground crew; third row from left: T/Sgt. Patrick, Capt. Tudor, Lt. Ryan, Lt. Williams.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

According to the materials John made available, on August 7th 1944 his father, James Ryan, was a co-pilot in the crew of Captain Tudor (464th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force). Their B-24 "Liberator" was nicknamed "All Meat No Potatoes". The nick name came from a title of one the popular songs of that time.

Lt. Ryan crew in the training base at Topeka, Kansas (end of 1943 or beginning of 1944).

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

The B-24, which Ryan flew, fell victim to the intensive heavy flak fire. According to the accounts of three other aircraft from the same formation, the B-24 received a direct hit over target in the left outboard engine. The engine fell apart. The bomber turned then on its back and began going down in a spin. Then the other crews lost sight of the mortally wounded aircraft.

Lt. James Ryan told his son after the war, that, while the crew had been trying to leave the falling aircraft, Capt. Tudor (pilot) and himself had fought to stabilise the machine in order to minimise the centrifugal force, so that the crew could get out. Thanks to the pilots' efforts the B-24 came out of the spin and kept falling in slow clockwise circles. Five airmen managed to bail out. The remaining five were either already dead, or wounded in the degree that made the bail out impossible.

POW identification card of Lt. James J. Ryan.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

While hanging under the safe silk canopy, Lt. Ryan observed the falling bomber and thought what would happen next. The chance of avoiding the capture was very small and he was seriously afraid of the hostile German population.

Very soon he has landed near an abandoned farm, far away from his crew-mates. He has hidden the parachute, the flying suit and other equipment that he no longer needed. He has decided to wait until evening - darkness would increase his chances. Then, dressed in a found jacket and straw hat, he left his hiding and tried to get as far from the crash site as possible. It did not last long before he was spotted by a German army patrol and was captured.

American POWs in the camp at Sagan.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

Louis Valente was the bombardier in Lt. Tudor's crew. In an interview given to John Ryan, he has described the shot down of his aircraft in great detail: "...I was suddenly thrown against a side wall of the bomber. I could not move. It seemed like eternity but the time when I was pinned to the wall by the centrifugal force must have been short. I wanted to help the front gunner and open his turret's door but I could not. Then the gunner, Sgt. Kramer, opened it from the inside. We knew we were in trouble and wasted no time. I have begun to wind the nose wheel door open but it was very difficult to do because of the the slip stream and we had to force the door open with all our strength. The aircraft was falling down upside down or was in a spiral - in our small compartment it was difficult to judge accurately."

"Captain Tudor gave the bail out order. Myself and Kramer had our chutes on already so we have dived into the open nose wheel bay immediately. Tudor got out through a top hatch in the cockpit. Ryan and Hollmann got our through the bomb bay. None else managed to leave the aircraft. I have learned later that Anderson, our engineer and top turret gunner, died from a direct hit from Flak. I do not know what had happened to the rest."

"I was falling down without opening my chute. The bomber was falling at the same speed in a clockwise spiral. I was afraid the aircraft could hit the opened chute so I waited until the B-24 was slightly below me. I still remember how quiet and peaceful was up there. I knew what would await me on the ground so I have enjoyed the moment as long as I could. I have landed close to Lt. Hollmann in a farmfield. There was no sight of none else nor the aircraft." "After landing I drew my Colt .45, although I could not hit a barn with it. Hollmann lost his gun a month earlier when he had to bail out over Yugoslavia, so he was unarmed now. He has advised me to put down the gun because it would cause more trouble than help us. As soon as I did it a few soldiers appeared that were led by a senior gentelman in a German WW1 style helmet. He shouted something like "Hans Hauk!" ("Hände hoch" - hands up) which must have been a request to surrender. We were searched and they searched Hollmann a bit longer because they could not find his gun. I wanted to get a cigarette from my pocket but one of the guards pointed his gun at me - I have understood it was not the best moment to smoke."

"We were taken to a battery of 88 mm flak guns. We have soon found out they were the ones who had shot us down. It was almost noon, so they gave us sandwiches. Two Luftwaffe officers arrived soon who took us through a village - its name was Annaberg, I think. When we walked through the village, a woman ran towards Hollmann and hit him on his head. I had still a piece of the chute on my arm and a small boy took it from me. We boarded a train and joined there two other Americans, who had been shot down too. Strangely, the Germans did not take my watch away from me and I managed to keep it with me through the POW time and it came home with me..."

Full name of the POW camp in Moosburg.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

Valente joined a large group of shot-down airmen, who were collected from all over occupied Europe and taken to Oberursel near Frankfurt am Main, where the central interrogation camp was located. Together with Ryan, Hollmann and Kramer he was then taken to Stalag Luft III in Sagan (today Zagan, Poland). Then they survived the 600-kilometres-long death march when, in March of 1945, the Germans evacuated the camp in the flee from the advancing Soviet Army. They were liberated at Moosberg, Germany. Then they were taken by aircraft to France where they stayed until the end of hostilities. In the end, they boarded ships and headed for home.

John Ryan with wife and son at the crash site of his father's B-24 - Lichynia, August 10th, 2001. John holds a souvenir piece of his father's B-24 that was found at the crash site.

(photo: Waldemar Ociepski)

John Ryan was very much interested to find out, where exactly his father had landed. An on-site research had to be organised in order to answer this question. Incidentally, the author of the article has contacted Waldemar Ociepski, a passionate aviation history researcher. Waldemar lives in Kedzierzyn-Kozle and has a lot of interest in the USAAF bombings in the area of Blechhammer and Odertal. He has made available a number of interviews taken from the witnesses of different American aircraft crashes. Some of the interviews came from the area of Gora Swietej Anny (Annaberg) but all witnesses pointed to a crash site near a village of Lichynia.

The meeting in Lichynia. Left to right: Michal Mucha, Waldemar Ociepski, Robert Ryan, John Ryan, Szymon Serwatka.

(photo: S. Dragula/"Nowa Trybuna Opolska")

One of the witnesses, Alfred Biela, remembered that it was a very warm day, when the bomber fell near Lichynia. The aircraft were seen from far away - they reflected the sunshine. Mr. Biela remembered an aircraft coming down in circles, because the engines on the left side have been damaged. He saw airmen bail out. When the bomber was still abour 500 metres above ground, an engine fell off. When the plane finally crashed, it caught fire and the ammo began to explode. According to this witness, the fallen airmen were buried in a village of Zalesie Slaskie. The documents stored in the local catholic church confirm, that on August 9th 1944 five American airmen have been buried there, who have died two days earlier.

The accounts of the witnesses could relate to the "All Meat No Potatoes" but there was no certainly about this. The key elements were a map produced by Mr. Ociepski and a copy of a German report provided by John Ryan, where the capture of his father was documented. Both documents pointed at the same location - a field near Lichynia.

The B-24 "All Meat No Potatoes" was well remembered by Mr. Gerard Ciupka. On August 7th 1944 he rode his bike to see if his aunt was OK after the refinery in Odertal had been bombed. The aunt was OK and both walked to the crash site near Lichynia. The ship was burned out and two burnt corpses could be seen in the fuselage aft of wings. Mr. Ciupka directed Mr. Ociepski to another witness, Mrs. Helena Janda. She worked as a nurse in a hospital that was located where the Pilgrim House is today in Gora Swietej Anny. Mrs. Janda could remember two American airmen that were brought to the hospital. Although she could not remember any names, one of these men must have been Capt. Tudor - the German report mentioned he had been taken to this hospital. Mrs. Janda remembered the airman to tell that the Gora Swietej Anny had been an orientation point for the American crews.

Mr. Maksymilian Makosz was another witness of the crash that could be found. He and his uncle were at the crash site as the first local people. Very soon an American airman landed in his chute next to them. He was tall and very fit. He looked like being very content that he had survived. Taking into account that Tudor was wounded, Valente and Hollmann landed far away from the aircraft and James Ryan surrendered only a few hours after landing, the person who landed near Mr. Makosz must have been Sgt. Kenneth Kramer. The witness remembered that when the airman took off his chute harness, a policeman riding a bicycle appeared who shouted from the distance to the American to surrender. They went to the village of Lichynia. Mr. Makosz met again the airman in the village. The prisoner was waiting at the steps of a small chapel near the house of the local administration head. Then Mr. Makosz came back to the burning wreck and he noticed then 22 small bombs painted on the nose. It was the 24th mission of Capt. Tudor's crew and the 23rd bomb must have not been painted yet.

Memorial stone in Zachary Tyler National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.

(photo: John Ryan via Michal Mucha)

The new cemetery in Zalesie Slaskie. The KIA airmen of the "All Meat No Potatoes" were probably buried in this grave along the soldiers of the Silesian Uprisings.

(photo: Waldemar Ociepski)

Modern view on the Zdzieszowice (Odertal) coking plant from a viewing point at Gora Swietej Anny.

(photo: Waldemar Ociepski)

This is the story of the crew of the "All Meat No Potatoes", recreated after almost 60 years. John Ryan came to Lichynia on August 10th 2001 to visit the place where his father had been shot down. He could also see the industrial complexes over which so many airmen' tragedies happened. He has paid a tribute to these, who had paid the ultimate price in the World War Two. Let us also remember the men who gave their lives so that we could be free.